Tattoos and fermentation rarely appear in the same conversation, yet across the world, they share a quiet kinship. Both are practices of transformation, crafts that reshape raw material over time through care and relationships to the land, the spiritual, and the community. Tattooing inscribes identity and ancestry onto skin, while fermentation preserves, nourishes, and binds communities through shared taste and ritual. Both create change, brewing something more than themselves through embodied knowledge passed between generations.

In northern Japan, Ainu women scraped soot from earthenware pots used for brewing to create tattoo ink, connecting two art forms via the hearth. Kalinga tattooists in the Philippines used fermented ink made from soot and sugarcane juice to hand-tap tattoos to mark bravery and beauty. The Makushi brewers in Amazonian Guyana applied tattoos as charms to shape the sweetness or “sting” of their fermented beverage. In Hawaii, the practices of tattooing and poi fermentation often parallel each other—another example of how across the world, the shared grammar of transformation is visible on skin and shared in drink.

These examples do not point to a single origin or universal meaning. Instead, they reveal how tattooing and fermentation often inhabit similar ritual and relational domains across global cultures. In examining these cultures, ink and drink operate as technologies of continuity and as ways communities stay in conversation with land, ancestors, and each other.

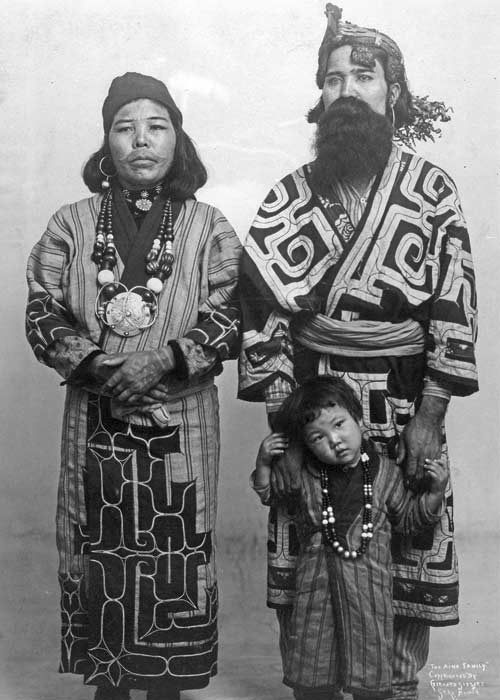

The Ainu of Northern Japan

The Ainu are an Indigenous people of northern Japan and the Russian Far East, with ancestral homelands in Hokkaidō, Sakhalin, and the Kurii Islands. Hunters, fishers, and foragers, the Ainu communities organize around the hearth as a domestic space and spiritual center, where food is prepared, stories told, and rituals maintained. Due to forced assimilation under Japanese colonial policy in the late 19th century, the Ainu culture, including tattooing, was suppressed by stripping it of its mythological and ethical context.

Among the Ainu, tattooing and fermentation emerge from the same physical and cosmological center: the hearth. Both tattooing and brewing fall under the domain of Kamuy Fuchi, the hearth goddess, who oversaw all domestic labor at the hearth, including cooking, brewing, and women’s rituals. Kamuy Fuchi is often envisioned as an elder woman who dwells in the fire itself.

Historically, Ainu tattooing was a gendered practice performed almost exclusively on women. Traditional tattoos were created by rubbing soot collected from the underside of cooking pots into patterned incisions. Lip tattoos, in particular, marked a girl’s passage into womanhood and were believed to offer protection against malevolent spirits. Using soot from the hearth reinforced the centrality of fire through domestic ritual, binding the tattooed body to the spiritual authority of Kamuy Fuchi.

Fermentation followed a parallel logic. Tonoto, a rice-and-millet beer used in ceremonial gatherings, was prepared exclusively by women. They offered prayers to the kamuy (divine beings of Ainu culture) and remained the sole caretakers of the beverage until it was formally presented to men during rituals. Brewing, like tattooing, was not merely a technical task, but a spiritual responsibility carried out under the watch of the hearth goddess.

With both practices centering around the hearth, the Ainu practices of both brewing and tattooing are not linked in any mechanical way. Instead, they are bonded by generations of care and attention from women, serving as important extensions of the very fire that animates Ainu life and culture, extending the hearth’s fire, memory, and spirit outward and into the body in multiple ways.

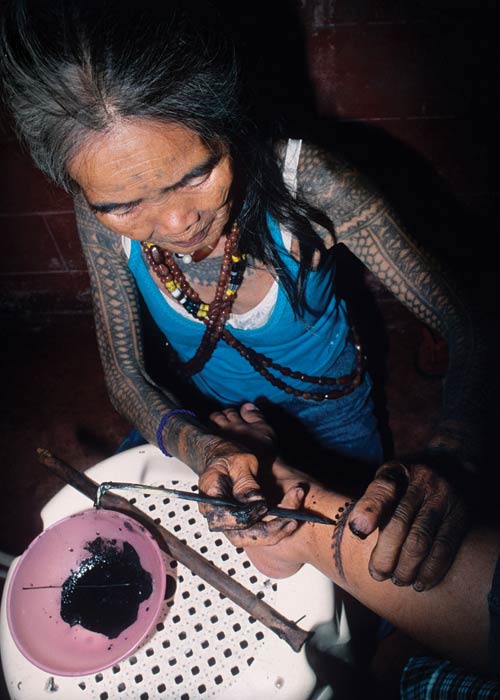

The Kalinga of the Philippines

An Indigenous people of the northern Philippines, the Kalinga live in the rugged Cordillera mountain region of Luzon. Known for their terraced rice agriculture, strong kinship systems, and, historically, headhunting practices tied to warfare and prestige, Kalinga communities have long marked social identity and life transitions on the body itself. Kalinga batok, a hand-tapped tattoo practice, has been passed down through generations.

Batok tattoos are applied by a mambatok, a traditional tattoo practitioner, using rhythmic taps to drive ink into the skin. These tattoos offer a different intersection of ink and fermentation—one embedded not in brewing but in the tattoo pigment itself. Traditional inks combined soot with water or plant-based liquids, and in some regions, sugarcane juice was used as a carrier. Once mixed, the ink was allowed to rest, and if the artisan used sugarcane juice, the mixture would begin to ferment into alcohol. This subtle change impacted the chemical composition of the ink, though adhesion and longevity of tattoo pigment in the skin are a biological and mechanical process.

The ink marks themselves carry deep social meaning. Grace Palicas is one of the few tattoo artists to train under the formidable 117 year-old Wang-od Oggay, a master mambatok of Buscalan. She explains that batok historically signaled bravery for men, “a kind of identity, because back in the day the men were getting tattooed only after an act of bravery,” and beauty for women. “We consider it like jewelry… to make us prettier, usually to find a husband.”

While batok is not directly tied to brewing and the ink is no longer produced as it was historically, fermented beverages such as tapuy (rice wine) and tubâ (palm wine) have long anchored feasts, healing rites, and social gatherings across the Cordillera. Tattoos and fermented drinks occupy the same ceremonial spaces, making moments of transformation and reinforcing communal belonging. Even when fermentation no longer shapes the ink itself, both practices reflect a shared cultural logic achieved through time, care, and skilled hands.

The Makushi of Guyana

The Makushi are an Indigenous people of the Guiana Shield region of South America, living primarily in the savannas and forests of southern Guyana and neighboring Brazil. For the Makushi, cassava (a starchy tuberous root) is a staple crop and the foundation of daily sustenance, social exchange, and ritual life. From planting to process to brewing and celebration, cassava binds households together through shared labor and flavor.

At the center of this is parakari, an intricate cassava beer made through dual fermentation with mold and yeast. Brewing is central to ritual life, communal labor, and social cohesion. Anthropologists have observed that participation in creating and drinking parakari is beyond social, representing a part of Makushi identity by engaging in this process of transformation.

Tattooing enters this world through kansku markings, tattoos designed as cooking and brewing charms. These tattoos are no longer widely practiced, having declined under colonial and missionary influence, but were believed to gift a woman with enhanced capacity to produce better fermented foods and drinks. Their motifs symbolized desired qualities of the brew itself with patterns depicting arthropods, such as bees and scorpions, giving sweetness like honey or perhaps a bit of kick, maybe a “sting” (yekî). In fact, in the Makushi tongue, the verb yekî has a double meaning, also referring to being intoxicated with alcohol.

Parallel traditions among related Cariban-speaking groups across the Guiana Shield strengthen this pattern. For example, Akawaio women also have tattoos regarded as charms to help them make sweet cassava bread and other drinks. Tattooed arms were considered necessary in order to prepare beverages, while a tattooed jaw gave them sweetness.

The social ritual of enjoying a drink in Makushi culture solidifies this by requiring that the beverage be shown to have been prepared under the right bodily and spiritual conditions. According to cultural tattoo anthropologist Dr. Lars Krutak, “A woman could only pass a drink to a man if her arm were tattooed.” Here, the connection between tattooing and fermentation is overt: body markings are active participants believed to shape the quality of the beverage, moving beyond metaphor to embed cosmology directly into daily acts.

Indigenous Epistemologies of Transformation & Broader Ritual Intersections

Across the Ainu, Kalinga, and Makushi cultures, tattooing and fermentation do not intersect by accident or coincidence, but appear within the same ritual and relational spaces where identity, responsibility, and transformation are negotiated. Hawaiian epistemology provides a framework for understanding why tattooing and fermentation so often inhabit the same cultural traditions without implying that any two cultures share the same meanings.

In Hawaii, kākau, a form of hand-tapped tattoo, inscribes identity directly onto the body. As Dr. Lindsay Malu Kido, a scholar of Indigenous body sovereignty, explains, “Our traditions are rooted in the physical expression of our genealogy on our bodies.” Through kākau, the body becomes “a living record of ancestry.”

At the same time, poi, made from fermented taro (Kalo), expresses kinship with Hāloa, the ancestral figure from whom Native Hawaiians trace their lineage. “In Hawaiian cosmology,” Dr. Kido explains, “kalo is Hāloa, our elder sibling, so feeding ourselves is an act of kinship.” Caring for a living food mirrors caring for family, land, and history.

Seen together, tattoos and fermentation function as relational practices, thus becoming ways of maintaining connection with ancestors, lands, and community, but also as a form of resistance. Per Dr. Kido, “Reviving kākau is an act of decolonization because it reclaims the body as a site of ancestry and authority rather than something controlled by outside moral frameworks.” Instead of a universal explanation, this framework helps clarify why, across cultures, bodies and ferments so often become sites where transformation and identity converge.

Contemporary Echoes

Today, tattoos and fermentation continue to shape identity in new ways. Brewers mark their bodies with hops, yeast cells, and scientific symbols. These are creative echoes rather than continuations of ancestral protocols. However, they still reflect the cultural logic that ink and drink both express a personal relationship with craft and the idea of transformation.

Brewing-related tattoos can also represent loss, growth, memory, and a cosmological connection. Sandra Murphy, head brewer and owner of Murphy’s Law Brewery & Pizzeria in Burleson, Texas, decided to pursue a career as an assistant brewer after her daughter died, and began a tattoo sleeve in her daughter’s memory.

“It starts at my wrist with the chemical formula for the primary element that makes up an ale yeast wall, then moves to wheat and barley stalks with my daughter’s birth flowers. At my elbow starts a hop vine that wraps up my arm with two butterflies in the mix and ends with a phoenix on my shoulder. There is a blue watercolor behind it all to represent water.”

Murphy says that joining the brewing industry didn’t just help her find her voice and reclaim her strength after a devastating loss: “It saved my life.” For many, finding their own voices can take the shape of tattoos.

Rachael Engel, brewer at Sound2Summit Brewery in Snohomish, Wash., says that the creativity and expression of identity behind tattooing were also big parts of her journey into the craft brewing industry. “I didn’t get my hop sleeve until after I came out as transgender and realized who I actually was,” says Engel. Like a hop bine, any journey upwards requires knowing where to find the light.

Practices of Transformation

Across the Ainu, Kalinga, Makushi, and Hawaiian stories, tattooing and fermentation emerge as culturally distinct yet deeply resonant practices of transformation. Whether marking lineage, signaling pride in craft, or navigating personal change, both tattoos and fermentation remain intertwined with the stories people carry into the world.

Each reshapes material and social worlds by inscribing identity, cultivating relationships, honoring ancestors, and sustaining community. Their intersections are not universal, but arise from shared Indigenous logics of embodied knowledge, ritual labor, and care carried forward through time.

Ink marks the body.

Fermentation marks the food.

Both leave traces of where we come from and invite us to imagine who we might yet become.

* * *

The Brewers Association and CraftBeer.com are proud to support content that fosters a more diverse and inclusive craft beer community. This post was selected by the North American Guild of Beer Writers as part of its Diversity in Beer Writing Grant series.

Frances Tietje-Wang is a fermentation chemist, writer, and educator focused on the cultural and scientific dimensions of fermentation. Their work explores how fermentation has shaped human history through identity, ritual, and community, while delving into the science behind it all.

CraftBeer.com is fully dedicated to small and independent U.S. breweries. We are published by the Brewers Association, the not-for-profit trade group dedicated to promoting and protecting America’s small and independent craft brewers. Stories and opinions shared on CraftBeer.com do not imply endorsement by or positions taken by the Brewers Association or its members.